History

Chartiers Country Club.

Nearly a century and counting.

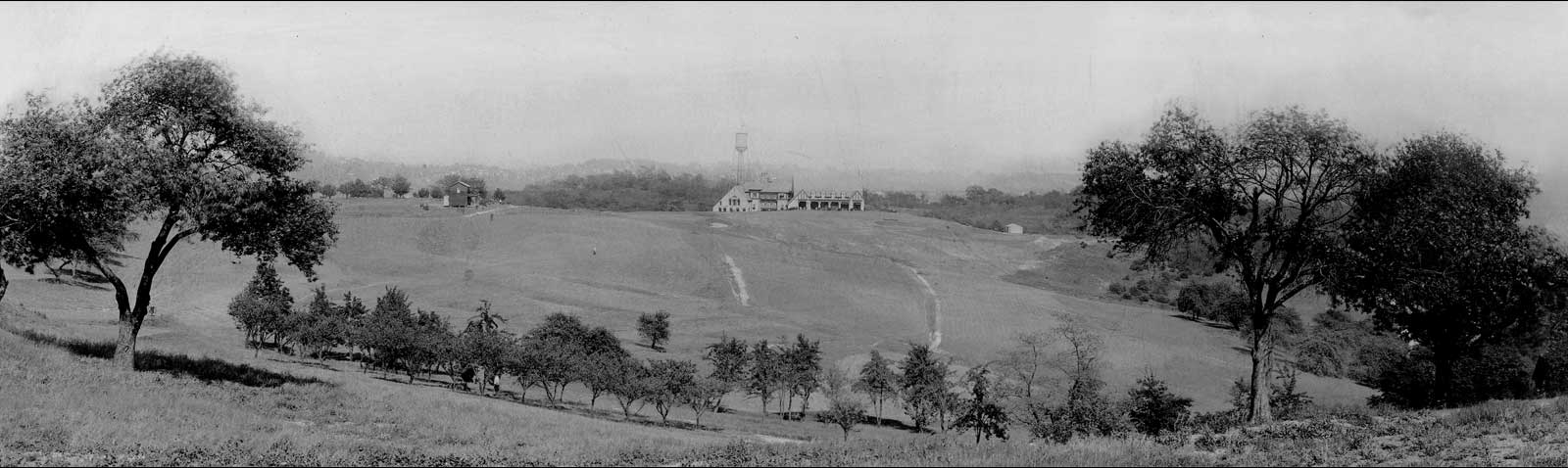

Nearly a century ago, two-time British Open Champion and acclaimed golf course architect Willie Park, Jr. traveled from Scotland to design a classic, championship golf course in the wooded hills above Pittsburgh. And so began Chartiers Country Club’s legacy as one of Pittsburgh’s most storied clubs, home to famous golf professionals and host to players like Ben Hogan, Sam Snead, Byron Nelson, Arnold Palmer and many more.

And today, that legacy lives on.

The present Chartiers Country Club traces its beginnings to the founding in 1924 of Chartiers Heights Country Club. But the club’s real roots, its very conception, reach back further in time to September 1901.

That reportedly is when golf was first played in the Chartiers Valley on a six-hole course in the borough of Thornburg. Frank Thornburg, who founded the town, established the course, which he called the Thornburg Plot, to attract prospective home buyers.

In 1902, Thornburg residents formed an unchartered golf club at the tiny course with membership limited to those living in the borough. Dues of ten dollars a year were levied on members to provide for up keep of the greens, general course maintenance, and improvements.

When it came time for Thornburg Country Club to buy the hilltop land for the new club, the treasury was not up to the task. So nine members whose names have been lost and forgotten put up a stake and personally took an option on the land from the coal company and the various farmers who owned the property.

Before work on the site could even begin, the road had to be widened, straightened, and paved. But that was a temporary measure and a more permanent solution to the access problem had to be found. Yet another committee was formed to get a new road built. The committee eventually managed to convince the Allegheny County Commissioners to construct the concrete road that is today’s Baldwin Road.

Apparently the site, which is roughly where Number 1 tee now is, was selected by the committee overseeing the planning and construction of the new clubhouse because it was the highest point of land on the property. But after ground tests, it was determined that the site was not suitable and the present location of the building was chosen.

While members of the building committee were searching out the clubhouse site they also were meeting almost weekly with the architect, Press Dowler, to review developments. Dowler eventually submitted a plan for a Colonial style clubhouse building which had one very serious flaw: it was beyond the reach of the club’s rather limited financial resources.

The board of directors had instructed the committee to have Dowler submit a plan that was to cost no more than one hundred thousand dollars. But if the architects plan were accepted as drawn, the building would have cost three hundred and fifty thousand dollars. The plan was rejected and Dowler went back to the drawing board ‐ literally.

The architect likely was simply following instructions, or at least what he thought were instructions based on the description of the clubhouse that Allen Fink put in the promotional brochure: “The present plans contemplate a number of sleeping rooms, single and in suite; a dormitory, an improved idea in locker rooms, a large assembly room suitable for dancing, movies, private theatricals, etc., dining rooms, grill rooms, wide porches, and an indoor swimming pool. Every detail of service will be perfectly provided for.”

Eighteen holes built over a rolling fairway, with large greens that will be a delight to the golfer and a test of his skill. No finer natural layout for a course can be found anywhere.

It was a description that any golfer inspecting the hilltop site would have had to take with several grains of salt. Even though by that time a lot of work had been done on the course (the brochure stated that “construction is proceeding according to schedule, ten holes now being ready for seeding”), it hardly was “One of Nature’s Beauty Spots,” another phrase the brochure’s author used to describe the property.

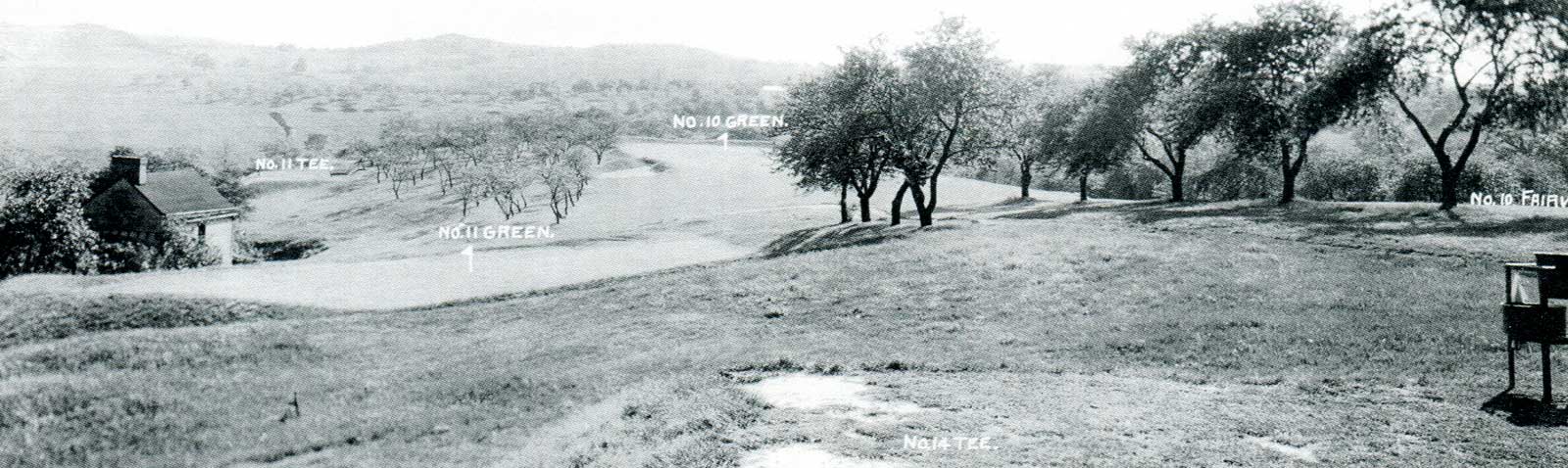

The hilly terrain made developing a course layout a formidable challenge. Park’s initial layout proved to be unworkable and was rejected. Eventually, he designed an eighteen-hole, six thousand three hundred forty-eight yard course that was accepted by the board

Work on the new course began in 1922 and a year later Thornburg Country Club members were allowed to play the first nine holes. So eager were the members to play the new course that they persuaded the board of directors to open the first nine even though some of the holes were not in the best playing condition. It was t w o more years before all eighteen holes were playable.

The courses early years were beset by many problems caused by the infertility of what had been farmland left uncultivated for too long, shifting soil, and poor seeding conditions, including at least one almost total seeding washout from prolonged and unusually heavy rains.

Conditions and topography led to several extensive changes in the layout and design of several holes in the first five years that the course was operating fully and by 1930 the course was beginning to attract local attention. Chartiers Heights president A. D. Robb was quoted in

The Pittsburgh Press on April 27 that year as saying that the course was in the “most satisfactory and healthy condition since the club’s inception.”

According to the Press story, written by John McMahon, improvements to the course included a complete remodeling of the ninth and fourteenth holes with “both pronounced better and sportier for the transformation.”

- Carts were not allowed on the course until the late 1950s and, before he could ride a cart, a member had to have a note from a doctor saying he was not able to walk the course. The club did not provide carts; members had to buy their own. They also had to pay the club for maintenance and storage.

- In the original course layout, Number 18 green was situated where the swimming pool is now.

- There used to be two water towers on the course: one near Number 17 tee (the base is still visible) that was torn down after the huge tower was built in Green Tree, and a smaller one near the clubhouse.

- There were wooden bridges over deep gullies on Number 5 and Number 13. The bridge on Number 13 was torn down during the Hassenplug renovation; the one on Number 5 was demolished earlier.

- The last tournament at Chartiers to draw a field of nationally ranked tour professionals was one sponsored by Ford Motor Company and area Ford dealers in 1964. Reportedly, when the Visiting pros read the scorecard and saw the shorter-than-they-were-accustomed-to distances, they promised to tear up the course. To which Arnold Palmer, apparently the only one of the participating pros who was familiar with the course, replied: “Wait until they get on the greens.”

- At one time there was a pond at the bottom of Number 4.

- Golf course greens always have been complicated structures. According to a report published when Chartiers’ new greens were being built in the early 1920’s, each green required on average fifteen tons of Cinders, forty tons of manure, twenty tons of sand, twenty tons of humus, fifty tons of topsoil, two hundred pounds of lime, and two hundred pounds of acid phosphate.

When Bobby Cruickshank, the “Wee Scot” who put Chartiersgolf on the map during his eighteen-years as club professional, announced his retirement in 1965, a great party was called for. A committee chaired by Ray Downey pulled out all stops in planning the affair, which many members today still insist was the greatest party in the club’s history. It is remembered not only as a fond farewell to a Chartiers institution but also a celebration that caused a surprise reaction from the guest of honor, who loved to party almost as much as he loved to golf.

There was no question that Cruickshank deserved a grand sendoff. When he arrived at Chartiers in 1949, he already had established himself as one of the premier players on the Professional Golf Associationtour‐ a tour that he was instrumental in starting, promoting, and developing.

Until the day he retired, he worked tirelessly at the club where he not only continued to play better golf than just about anyone else in western Pennsylvania but also became a tough, respected, and very effective teacher of the game. He taught not only Chartiers members and their families but also golfers from other clubs and courses throughout the area.

Cruickshank came by his “Wee Scot” nickname honestly. Born in Scotland in 1894, he was only about sixty-three inches tall but used a forty‐four inch driver.

He was leading money winner on the PGA Tour in 1937 when he won the Los Angeles, Texas, Arkansas, and North-South opens and the National Four-Ball Tournament with teammate Tommy Armour. But it was in the United States Open tournament that Cruickshank made his reputation as a tough competitor.

In the 1923 U.S. Open Championship he tied the legendary BobbyJones on the seventy-second and final hole of regular play to force an eighteen‐hole playoff. He lost to Jones by one stroke on the last playoff hole. (It was a match many believed launched Jones’ fabulous career. Prior to the1923 Open, Jones had not had a great deal of success on the tour.)

Cruickshank tied for fourth place in the following years Open, tied for second in 1932 when he lost the Open title to Gene Sarazen who scored a double eagle in the final round, and tied for third place in 1934.

In that 1934 Open at Merion Golf Club in Ardmore, Pennsylvania, Cruickshank hit what the Sixty-Fifth USGA Open Championship program called “Cruickshank’s Lucky Shot.” But it was one that was decidedly unlucky for the Wee Scot. It occurred on the eleventh hole of the final round of the match and Cruickshank was tied for the lead with Sarazen. Cruickshank hit his approach shot into a brook that partly encircled the green. But the ball hit a rock in the brook, bounced into the air and on to the green. That was the“lucky” part of the shot. Cruickshank was so elated that he shouted, “Thank you, Lord” and threw his club high into the air. The account published in the program continues with the “unlucky” part:

Alas, the club came down and struck him on the head. He played the last seven holes in five over par and finished two strokes behind the winner, Olin Dutra.

After being named club professional at Chartiers, he won Tri-State PGA titles in 1949 and 1950. He broke the Chartiers course record with a seven-under-par sixty‐three on September 24, 1952 while playing with then‐president William O’Dell and Henry Mchaide. By doing so, he broke the previous record of sixty-four, which he held along with former Chartiers pro Dick Shoemaker and Jim Gardner, the 1951 club champion. Both The Pittsburgh Press and Port‐Gazette carried stories of the event.